I was supposed to have a day off work that Friday. I was supposed to spend it off social media too. But I did neither, and I’m very happy with that.

The day before, the United Kingdom’s House of Lords (parliament’s second chamber) published a report by its Adult Social Care Committee called “A gloriously ordinary life’’: spotlight on adult social care.

“A gloriously ordinary life” – these words tell you already this isn’t the usual report we see all the time. This report is meant to be read and understood.

Could someone ping the UN please. I mean, whatever the world has come to when you don’t need a PhD. from three different universities to be able to read and understand a report about peoples’ lives.

The report is about adult social care in the UK; care for adults with disabilities and for old people. Care provided by family members and other informal carers, and by formal care services. This alone makes the report valuable. Add to it the way it was produced (in a close collaboration with “experts by experience”), the extensive research and data used to illustrate its points, and once again its language – and this is a must-read for anyone with an interest in social care, public services, or disability rights.

The UK social care system’s ability to provide research and data is something that makes a Continental person envious. “Lack of data” is a regular and long-standing complaint from European disability organisations and others in the field. Regular, long-standing complaint that doesn’t seem to be getting even close to being heard, let alone resolved.

The report draws extensively on the work of Social Care Future. I recently talked with Neil Crowther about what Social Care Future is, how it works, and about some other topics. That conversation may be relevant to listen to alongside the report.

I spent the day after the report was published reading it and tweeting about it. It was a glorious experience. I saw a great report clearly articulating issues that matter. I found a wealth of new research and data that can be used and referenced. I discovered new points of view, and ways to express them. I indulged in reading points I make regularly, expressed with great ease and strong evidence.

“people are stripped of all choice and control when it comes to determining the terms of their most intimate relationships”

My timeline today is a love letter to the authors of this @HLAdultCare report https://t.co/62K9IyucyN

— Milan Šveřepa 🌻 (@misver) December 9, 2022

But above all, I saw a text that is clearly meant to be read and understood, including by people who are the subject of it.

The report is a testament to what it means and what can be achieved when participation and collaboration are done right.

It is a benchmark for anyone writing about social care and public policy in general.

Excerpts from the report

These are mostly selected for catching my eye with an expression, or providing useful data about an issue, or making a good point about something of relevance. Perhaps you will find them useful too. Emphasis is mine.

Third, we want to see a system that is not based on the assumption that families will automatically provide care and support for each other because no other choice is open to them. This means that people should be able to choose what care they receive and from whom—and support should be available equally, whether they wish to draw on unpaid care, on paid care, or on a mix of both. (page 5)

Little is known about adult social care

4. Tragically, despite these recent reforms, very little has improved for those who depend upon or provide adult social care.

5. The reason for this might seem obvious. Unlike the NHS, which cares ‘from cradle to grave’, we collide with adult social care usually at a moment of crisis, of unexpected transition, when our lives appear to be changing for the worse. Unlike the NHS, little is known about who is in charge of adult social care, how it works, how it is paid for and what help we might get.

6. Whereas we celebrate the NHS and take pride in its history and achievements, adult social care has largely been missing from the heroic account of the welfare state. Seeking help from adult social care seems a mark of failure and dependency, and a last resort. With dependence seen as the norm for disabled adults and older people, and as long as women stayed at home to provide care and support, there appeared to be no reason to publicly acknowledge the importance and value of social care.

9. We have asked: who cares? The answer is, in most cases, the family at home and friends in the community: the ‘unpaid carers’. Recent analysis of data from 2001 to 2018 revealed that 65% of adults have provided unpaid care in their adult life, which increases to 70% for women. The average person now has a 50% chance of becoming an unpaid carer by the time they reach 50.

“Unpaid care”

11. These are relationships that are hugely diverse. From a wife who cares for her husband when his health starts deteriorating, to a daughter providing support to her parents with chronic medical conditions: unpaid carers are not “others”; as one witness told us, they are “like you or me.” The term ‘unpaid carers’ is a barely adequate description of the many millions of women and men who provide care and support to disabled adults for a lifetime, or who become carers for older people who, sometimes suddenly through stroke, dementia or many other causes, become reliant on care and support. Their voices are hardly heard and they are, for the most part, invisible to those of us who are not in the same situation.

Box 1

We heard from many witnesses that the term ‘unpaid carer’ is flawed, because many do not find that this label reflects the nature of the care and support they provide. As one witness explained to us, providing care is often instinctive: she employed the analogy of “someone just literally tripping up on the pavement and you put your hand out to catch them.” Labelling this as ‘unpaid care’ was, she said, unnatural. Another witness explained that she found the concept of being “cared for” very difficult to accept, because of the passive role it pins onto the person with care needs; when in reality, caring is a dynamic relationship, in which the person with care needs can also be and often is a source of support to the unpaid carer. Many carers, therefore, prefer to use the word which best describes their relationship to the person they provide care for, such as ‘mother’ or ‘husband’.

Real-terms spending reduction, providers proliferation

20. Local government funding for adult social care, however, is not keeping pace with demographic pressures, and increasingly, access to care and support is rationed, driven by a 29% real-terms reduction in local government spending power between 2010/11 and 2019/20. Estimates show that this has caused a drop of around 12% in spending per person on adult social care services between 2010/11 and 2018/19.

22. At the same time, the market in social care has proliferated with an estimated 17,900 organisations involved in providing or organising adult social care in England as of 2021/22. The quality of care is therefore highly dependent on the culture, strategic leadership and financial resources in each locality, leading to vast regional inequalities.

25. The choice for people is stark in the extreme: go without or self-fund, or more commonly, when it is a possibility, rely on family or friends. Pressure is growing inexorably on unpaid carers to ‘step up’ and provide the care and support that no one else will. And while friends and families are often prepared to provide support out of love, they often find that they must do so out of inevitable necessity and with insufficient support. The huge weight of evidence we have received shows that people are stripped of all choice and control when it comes to determining the terms of their most intimate relationships.

29. One significant problem which we heard many times is that there is little support for carers to navigate the system, which means that they often find themselves endlessly searching for advice and information, despite the very little time that they have to do so.

31. There is above all, therefore, an imperative to revalue what makes adult social care work at its best: the quality of trusted and reliable relationships. This in turn requires a move away from what was described as a transactional system – in which care services are clearly defined and time-limited.

33. This is work in progress. Some local authorities have led the way in implementing this vision. They told us that it meant valuing and treating disabled people and older adults as equals, and seeing them as individuals who could be enabled to live the best life they can—not as problems to be solved.

39. At the heart of the adult social care system should be the objective of enabling independent living. This means that disabled adults and older people have the same choice and control over their lives as non-disabled people. We explore this in Chapter 6, as we examine how to further promote the transformative power of direct payments, and how the solutions offered by accessible and inclusive housing, including with the promise of digital technologies, need to be scaled up. Achieving this transformative change requires a broader, more inclusive view of social care, going beyond the provision of formal services.

Invisible

47. A Carers Trust survey found that 91% of unpaid family carers felt ignored by the Government. Many told us how they also felt dismissed and alienated by the services themselves. We heard that “the invisibility of social care perpetuates the despair and does little to promote dignity, choice and fulfilment of life.” There are risks of increased loneliness, isolation, anxiety and depression due to chronic feelings of being undervalued. One unpaid carer said: “Most of us are desperate. Most of us are drained. Most of us are in a state of grief. We need support, we need recognition.” As well as having health implications for the individual carers, this increases the risk that care responsibilities are passed on to local authorities.

48. Many stakeholders argued that the adult social care sector is more than invisible: it is also the subject of misconceptions among the general public, who often do not realise the diverse, versatile and positive role that the sector plays in society. Lucy Campbell, from Rights at Home UK, described the dominance of care homes in the media and political discourse, which does not reflect the variety of circumstances that exist within social care.

51. First, the need for, and access to, social care is often viewed as something affecting other people—’them’, not ‘us’—and not a common cause for national debate or widely understood in all its complexity. This is because most people’s experience of social care is formed out of a crisis, when they are not best placed to think strategically. We were told that “many people only begin looking for information about services once they have reached a crisis,” with detrimental consequences for their own health and wellbeing. In other words, people who need to access social care are often on the backfoot from the start.

54. To an extent, this is an understandable and human reaction. Just as there is a natural aversion to thinking about or preparing for old age, there is a general reluctance as a whole in the community to think about when and how social care might be needed. The Centre for Care at the University of Sheffield argued that “there is a lack of public awareness about adult social care” that is born of several factors such as an unwillingness to think about a time where social care is necessary, fear based on negative news stories and stigma related to being in receipt of care. The Local Government Association (LGA) pointed to the fact that many people do not know what adult social care is and how it operates; many people do not give much thought to their possible future social care needs; and people deliberately avoid thinking about potentially difficult future circumstances, which is also attributed to the way social care is portrayed by the national media. One expert by experience went further, arguing that “‘it is more dangerous than invisibility, I am afraid. I think it is that people think that they know what it is but that it happens to other people.”

62. This lack of visibility is partly the reason why there is a lack of parity of esteem between adult social care and healthcare. For instance, the Homecare Association noted how in one care home, workers had been allowed to add the NHS logo alongside the care logo on their uniforms. This made a substantial difference to the respect they gained from other professionals and service users. Meanwhile, Ministers tend to be more preoccupied with healthcare as the NHS has a higher resonance with the public. As a result, social care is often perceived to be “in the shadow” of the NHS and as an “enabler for a more streamlined healthcare service”.

Fragmented, unstable, “makes no sense”

65. Adult social care is also provided by an unstable market. Most social care services are delivered by independent sector home care and residential care providers, which are mainly for-profit companies but also include some voluntary sector organisations. It is the responsibility of local authorities to commission care from those providers, and therefore to ensure that the local care market is healthy and diverse. In 2021/22 around 17,900 organisations were involved in providing or organising adult social care in England, delivered in an estimated 39,000 establishments. In addition, around 70,000 direct payment recipients are estimated to be employing their own staff.

66. This fragmentation creates massive confusion at every level of the service.

72. There is no doubt that underfunding has led to the rationing of care, restricted choice and a loss of quality of life.

73. Unpaid carers are on the front line in every respect. Every cut in funding affects them directly. As we have already made clear, they inhabit a world in which the social and economic contribution of unpaid carers is taken for granted, regardless of carers’ individual challenges or the choices that people who draw on care might make about who they would like to support them.

75. The fact that so much happens and is provided out of sight means that the trust that exists between the public and the NHS is not replicated in terms of social care. This is reflected in the fact that so many experts by experience, both individuals with care needs and unpaid carers, feel that they are ‘battling’ and ‘fighting’ the system at all times. “don’t understand the hardships we face as unpaid carers or the stress and difficulty of being a parent carer.”

Disability assumptions

86. Disability is frequently associated with false assumptions made about the amount of care disabled people need and how productive they are. This contributes to an overarching narrative that portrays disability as a problem. A study carried out by disability charity Scope in 2018, for example, found that up to 75% of respondents thought that disabled people need to be cared for some or most of the time. Around one in three (32%) people said that they thought disabled people are not as productive as non-disabled people at least some of the time. The survey also found that the public’s understanding of the prevalence of disability is inaccurate. The proportion of disabled people in the general population is 22%; yet six in 10 respondents thought it was 20% or less, and four in 10 respondents thought it was 10% or less.

99. Disability charity Leonard Cheshire, for example, pointed to research finding that the lives of working age disabled people have been curtailed due to inadequate social care and support over the last 12 months. This has meant that 41% have not been able to visit family and friends; 36% have been unable to leave their house, shop for food or clean their home; 33% have been unable to partake in their hobbies; and 28% have not been able to prepare a meal.

101. We heard that as a result, social care assessments are too often a “tickbox” exercise: services are provided to cover essential needs once a person meets the right eligibility criteria, or ticks the right box, making for a highly impersonal system that leaves no room for a person to express how they could be empowered to live a meaningful life beyond basic personal care. This is aggravated by local authorities facing reduced budgets: they are more likely to act as ‘gatekeepers’ to keep people out of the system. This is missing the ‘social’ aspect of care, and instead makes for what one expert by experience described as a “medicalised” model of care:

“The thing about the NHS is that it is very transactional. Even if it is positive like having a baby, it is still transactional. You want some support, you want this, you want that; it is an exchange, and you get a result. We try to apply the same principle to social care … but nobody has the conversation about what would really enable you to keep living the life you want to live.”

104. This often happens despite the best efforts of social workers. Many witnesses described to us the valuable work carried out by some social workers and local authorities, who support the vision of adult social care as an enabler for people to live an equal life, but eventually find themselves unable to achieve this vision in the current system. One expert by experience told us that many social workers who have “a creative thrust and social justice” are met with a system that requires them to become “checklist completers and box-tickers.” The same witness concluded: “They want to be able to use their skills, and support people in a progressive and empowering way. I think the system is failing them as well.”

105. In this system, access to appropriate social care services was described to us as extremely difficult to achieve. Because local authorities carry out assessments of needs based on narrow eligibility criteria, people are pushed out of the system until their needs become extreme and urgent.

109. Often, as a result, people feel powerless in the face of their local authority and some live in constant anxiety that services will be reduced or altogether removed from them. One expert by experience described to us that whenever they contact social care for a review, advice or a support, they fear their budget will be cut: “Just by contacting them and them getting more involved in my life, suddenly things might start getting pulled away.”

The role of friends and families

110. This lack of choice and control extends to people’s relationships with their friends and families. Against a background where there are 165,000 vacancies in the social care workforce, we were told that there is an expectation from local authorities that families will provide most of the support for their person they care for, and that this support can be relied upon and used as a way of cutting budgets or minimising expenditure.

111. There is, therefore, an embedded narrative by which care and support should come from families first, leaving no room for individuals with care needs or unpaid carers to exercise any choice over their relationship with each other. “Carers feel that they must do whatever the local authority says the local authority will not do, or else that they risk their loved one being taken away and being stuck in a care home.”

119. What we do know, however, is that the system is not designed or prepared to respond to the needs of this group. People ageing without children, as a result, often fall into the formal care system earlier. The organisation Ageing Well Without Children said that people ageing without children are significantly more likely to move into a care home, at a younger age and a lower level of need, “simply because there are no other options out there.” This is symptomatic of a system that leaves little choice or control to those who do not wish to, or cannot, rely on the care and support of unpaid carers.

“State could not afford to replace unpaid carers”

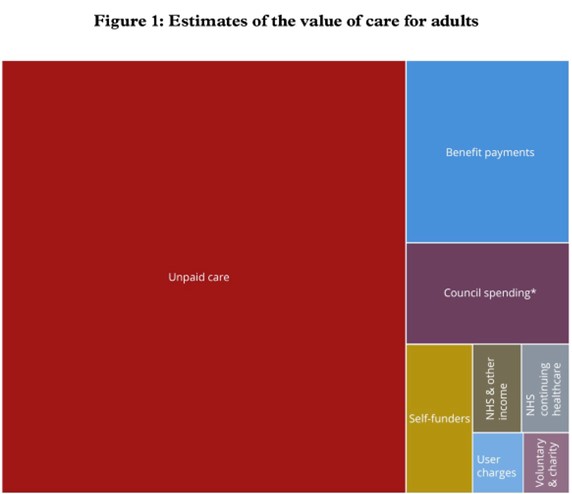

124. Putting an exact figure on the economic value of unpaid care is difficult and estimates vary. The ONS estimates that the gross added value of unpaid care in the UK was £59.5 billion in 2016. The Nuffield Trust wrote that unpaid carers provided care worth £193 billion per year during the pandemic. Professor Sue Yeandle, the Director of the Centre for International Research on Care, Labour and Equalities (CIRCLE) pointed to a figure of £132 billion per year, which she argued was the product of a methodology that was considered the best method for the purpose.

125. What is certain is that these figures are significant, and that the state could not afford to replace the work of unpaid carers with formal care services. Dr Valentina Zigante, from the London School of Economics, told us: “We know very well that carer breakdown is what causes people to need to go into residential care. It is massively costly in economic value to society.”

134. The chances of not being able to work increase as more care is provided. Six in 10 of those who are caring for 35 hours or more a week are not in work, three times the rate of those caring for less than 20 hours a week. Those caring for 20 to 35 hours a week are also less likely to be employed, with around a third not in work or not able to work. Of those carers who are working, those with higher caring responsibilities (more than 35 hours or 20 to 34 hours) are more likely to work part-time than those providing lower levels of care (less than 20 hours): 43%, 32% and 29% respectively.

136. The Joseph Rowntree Foundation shared statistics that clarify the link between unpaid care and poverty, particularly for unpaid carers who provide more hours of support: the organisation’s research found that in 2019/20, 44% of working age adults who were caring 35 hours or more a week were in poverty. This compares to 21% of non-carers.

138. Many carers stressed that Carer’s Allowance is the lowest benefit of its kind, which is reflective of the value that is placed on unpaid care.

139. We also heard that unpaid carers face significant health challenges, both physical and mental. They are more likely to be unwell, frail and at risk of vulnerability. One unpaid carer told us: “I can honestly say that I have been exhausted for 22 years. I have not slept for 22 years. I have not had a respite for 22 years.” Research carried out by Carers UK based on unpaid carers’ responses to the 2021 GP Patient Survey confirm this: it found that 60% of carers report a long-term health condition or disability compared to 50% of non-carers. Personal health is neglected as the focus is relentlessly on the daily need to provide care to a partner, friend or member of their family. The Nuffield Trust also noted that the 1.3 million people who provided more than 50 hours a week of unpaid care during the pandemic face an impact on their health equivalent to the loss of 18 days in full health for every year spent caring.

140. There are also impacts on mental health. CLOSER’s research noted that unpaid care is linked with lower levels of baseline and follow-up wellbeing measures. A recent survey carried out by Carers UK found that 30% of carers said their mental health was bad or very bad; and 29% said they felt lonely often or always.

141 “If we really deliver £132 billion to the economy through the work we do, that saves every UK taxpayer about £900 a year in tax. Are you just going to abandon those people?”

148. This is compounded by the fact that the social care system makes it very difficult for unpaid carers, both to identify support for themselves and to organise formal support for the person they care for. We were told that the social care system makes no sense, with one witness recounting that he was given 32 pamphlets in his local hospital after he introduced himself as a carer.

“We do not believe new law is necessary”

159. We do not believe that new legislation is necessary. Existing laws must be enforced and must achieve their intent.

163. To achieve this, the national discourse will have to change. As one witness put it: “We have to stop thinking about going to social care as a disaster. Social care is an enabler.”

187. Adult social care is rarely celebrated as a rewarding and fulfilling career. We were frequently told that adult social care lacks clearly defined career pathways and gateways into more senior roles. Significantly, there is no professional recognition or certification of skills acquired in many adult social care roles. All these factors act as a deterrent.

208. We propose the creation of a Commissioner for Car and Support to represent all of those drawing on adult social care, which includes older people, disabled adults and unpaid carers. This Commissioner should undertake the following roles:

- promote awareness of and champion the rights and interests of older adults, disabled people and unpaid carers;

- challenge discrimination against older adults, disabled people and unpaid carers;

- encourage best practice in supporting older adults, disabled people and unpaid carers; and

- advise on whether new legislation prejudices older adults, disabled people and unpaid carers.

212. Wellbeing is defined as relating to the following:

- personal dignity;

- physical and mental health and emotional wellbeing;

- protection from abuse and neglect;

- control by the individual over their day-to-day life, including over the care and support that is provided to them;

- participation in work, education, training or recreation;

- social and economic wellbeing;

- domestic, family and personal relationships;

- suitability of living accommodation; and

- the individual’s contribution to society.

213. Other general responsibilities of local authorities as outlined in the Act include preventing the development of needs for care and support,…

214. Local authorities must effectively assess unpaid carers when it appears that they may have a need for support.

What life could look like

219. Professor Jerry Tew, who carried out research on the impact of the Act for the Department of Health and Social Care, told us that instead of focusing on what a better life could look like and how to get there, assessments consist of ticking off as many deficits as possible in order to claim services. People feel the need to focus on and emphasise their challenges as much as possible in order to access support that is guarded by strict eligibility criteria.

223. The tangible explanations for the shortcomings of the Act start and finish with funding.

227. An assessment should denote “a collaborative exploration of what a good life would mean to a person and how this might be achieved,” he wrote, instead of merely establishing a person’s eligibility for services based on narrow criteria.

Elusive grail

236. Integration is an elusive grail.

244. This has the potential to bring more effective services that are tailored to the needs of all local communities, but our attention was brought in particular to the possible benefits for rural areas. The nature of the care needs of rural residents does not differ from the rest of the population; but we were told that rurality creates “substantial differences” when it comes to meeting these needs.

Co-production

253. By moving social policy from its present detached position to a new model of co-production, the benefits of better design and delivery will benefit everyone. Co-production is one of the most urgent areas already within reach of change. It is grounded in a fundamental principle: older adults drawing on care to live as full lives as possible. This underpins the greater autonomy and respect that we also seek for the unpaid carer.

254. To achieve this, social care services must move from a transactional exchange to one which explicitly values and builds on positive relationships. To enable this, our attention was frequently brought to the principles and practice of co-production—a process in which decisions are made together as equal partners—through which disabled people and older adults can make their own choices and lead chosen, ordinary lives.

255. At the individual level, co-production means that people who draw on care can make better choices when it comes to designing and delivering their own care, in a process that places power and decision making into their hands. It ensures a more sustainable and effective service for the future.

256. Co-production also makes for better social care policy. The most systemic challenge, therefore, is the need to change the way social care policy is made. People who receive care or provide it currently have little or no voice or locus in saying what works best.

258. Moreover, we heard from experts by experience that they are often presented with services that are considered by social workers to be sufficient to meet their needs but might in fact be irrelevant or inadequate. One witness told us: “I am not seen as someone who is expert in me.” She recounted how, as a younger woman with mental ill health, she knew that acupuncture, a gym subscription or a walk on the beach would help her to get better, but social services would only offer her a day service, which she did not find helpful. “The starting point is that they do not listen,” she said. The National Care Forum also emphasised that people are not “properly” listened to when it comes to understanding what they want and need from care and support services. The consequence is that older adults and disabled people too often receive a service that does not respond to their needs. In the long term, this is ineffective and costly.

Re-establish “social” in “social care”

265. One expert by experience explained to us what a co-produced assessment should feel like in practice: “I would like to abandon all the forms… This is my ideal world and I would start with the person. It would just be so nice if you went and asked the person, ‘What are you hoping to achieve, and what would help you to get there’—two really simple questions. We do not need all this, ‘Tick here,’ and, ‘Tick there.’” This would be more aligned with the purpose of social care than current processes. In essence, it re-establishes the meaning of ‘social’ in ‘social care’.

266. The LAC network also told us that there have been several independent academic evaluations carried out on the model since 2009, which have consistently shown reductions in: visits to GP surgeries and A&E; dependence on formal health and social services; referrals to Mental Health Teams and Adult Social Care; safeguarding concerns; evictions and costs to housing; smoking and alcohol consumption; dependence on day services; and out of area placements.

268. …when the council’s meals on wheels provider gave notice on their contract, he was initially tempted to find another partner to deliver the same service; but then decided to first engage with each person who received the service to find out if they could find an appropriate alternative in the local community. From lunch clubs to local pubs running a group: “For every single one of them, we were able to identify a means by which they could engage with their local community, so that they were able to address that need and ensure that they received meals,” he told us. We heard that this “fine-grained” knowledge of local communities is what has been lost in social care.

269. This ‘micro-provider’ initiative has been extremely successful, and ranges from groups taking people with dementia out to give their carers a break, to peer support groups for people with mental ill health. There are currently 849 micro-providers registered on Somerset City Council’s community directory; and the additional capacity that has been created is saving the council around £2.9 million per year.

275. Co-production is a key way to enable individuals with care needs to codesign the care and support they receive at a personal level, but it can also be used at a policy level, to ensure that local and national reforms are grounded in lived experience.

276. Policy that is co-produced with people who have lived experience, like care that is co-produced with the individual, is more likely to be effective.

Clarity of purpose

287. The King’s Fund analysis of the success of the Wigan Deal states that “above all else, the Wigan Deal is a story of profound cultural change within the council and its partners.” This came from a new set of “positive beliefs” about the purpose and outcomes of adult social care, and trust in the potential of staff and local residents to bring about the necessary change. The council succeeded in enabling this cultural change because it consistently embedded its new narrative across the local authority. The King’s Fund describes that “a common vision was forged early on” and “a clear narrative” was developed for all staff to refer to.

288. The importance of having a clarity of purpose and a cohesive narrative to steer local authorities’ work in adult social care was also highlighted by Professor Tew, who argued that ensuring the “crystallisation of a vision” is key to successful change.

289 Making it Real takes the form of a set of principles called ‘I’ statements, which describe what good looks like from the perspective of people with care needs; and ‘We’ statements, which describe how organisations can meet the ‘I’ statements. All of the ‘I’ statements have been co-produced, meaning that the framework can be used as a tool to frame the conversation in a way that ensures a vision, purpose and focus that are rooted in co-production.

301. Much of this chapter emphasises the need to make what exists already to support independent living work better and universally, rather than being confined to instances of local good practice. In many cases, this means putting the choice of a personal assistant through direct payments within the reach of more people.

302. Alongside personal assistance, accessible and inclusive housing is key to enabling independent living.

Box 8:

ENABLE Scotland: Best practice in enabling the recruitment of personal assistants ENABLE Group provides self-directed health and social care to people in Scotland, through the PA model. ENABLE supports individuals in planning and designing the services they want, so that they can build their own bespoke team of PAs. The CEO of ENABLE Theresa Shearer told us that the main barrier to implementing a PA scheme is the lack of confidence that individuals and families have when it comes to being a recruiter and an employer. The organisation therefore runs an internal recruitment agency that facilitates the recruitment and onboarding processes for PAs. The agency works to people’s demands and criteria to ensure that the personal assistants hired are tailored to each individual’s needs. In parallel, the agency ensures that it attracts the right people into the profession. Individuals are recruited for their values and experiences, but not necessarily their social care experience. The emphasis is placed on their soft skills. ENABLE also pays PAs more than the Scottish living wage. According to Theresa Shearer, one-third of the organisation’s workforce earns between £11 and £12 an hour. ENABLE’s model, therefore, ensures that older adults and disabled people can recruit PAs that are right for their individual needs, without worrying about the recruitment process or human resources-related challenges. It also means that those joining the recruitment agency are driven by the right motivations, and that they have the appropriate soft skills to be a PA. This in turn enables personal assistance to become more attractive as a profession.

Housing

332. General Comment No. 4 of the UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights enshrines a human right to adequate housing. However, for people with care needs and disabilities, this human right has never been within reach. For decades the lack of accessible and inclusive housing, the failure to invest strategically and sustainably in ‘Care and Repair’ schemes and the failure to plan at market level for an ageing society which wants to remain independent for as long as possible and ‘age in place’ and therefore needs housing which is flexible and adaptable, has not been a significant housing priority. The voice of disabled adults and older people has simply not been taken into account when housing is planned or designed. Too often, people having to make a sudden choice about where to move to are unaware about the alternatives to institutional care offered by supported housing or adaptations to existing homes.

334. At transitional points, particularly in relation to discharging patients from hospital into appropriate and safe accommodation, one of the greatest failures in health and social policy has been the neglect of housing as a key determinant of what is necessary and possible. This is exacerbated by the lack of affordable, accessible and inclusive housing and supported accommodation.

338. Social housing is particularly pressured, with long waiting lists. Over one million households are waiting for social homes. Last year, 29,000 social homes were sold or demolished, and less than 7,000 were built.530 Witnesses emphasised that the Government should increase availability of affordable and social rented housing.

342. One exception to this trend is London, where higher accessible and adaptable standards have been the default for many years. From 2004 to 2016, the London Plan included requirements for developers in the capital to build homes to the Lifetime Home standard—a concept developed in the early 1990s by a group of housing experts, and which included 16 design criteria that could be applied to new homes to ensure that they were inclusive, accessible, adaptable, sustainable and good value. In 2016, following the Government’s review of housing standards, the London Plan was reviewed to reflect these new standards. The 2021 plan requires all new residential dwellings to be accessible and adaptable, as per the M4(2) standard described below; and at least 10% of new dwellings to be wheelchair accessible. However, an overall lack of affordable social housing in London means that, even if standards are appropriate, supply is still an issue.

345. One proposed solution we heard was that of collaborative housing, which is more available in other European and North American countries. However, it is increasing in popularity in the UK, for example with Housing 21’s programme of older persons’ cohousing development in areas of multiple deprivation in the West Midlands. Early findings of a study of cohousing indicated that collaborative housing models encourage a sense of community that engenders mutual support and residents “looking out for” each other.

346. Better supported housing would also help alleviate the situation. Supported housing gives disabled and older people choice about their lives, enabling them to live in a home environment rather than institutional settings. Better supported housing would also remove the stress that would otherwise be on institutional care, such as care homes and respite centres. According to the Equality and Human Rights Commission, housing that meets people’s requirements will save on health and social care costs in the future, as well as considerably lowering the cost of adaptations when they are needed.

347. Case studies show that when residents are given choices, such as who they want to live with or what they want in their individual kitchens, their quality of life improves. In order for the market to be able to deliver cost effective supported housing that also promotes independence, we heard that commissioners “need to be able to take a strategic overview rather than purchasing care and support based on short-term considerations of unit price.

362. Unpaid carers keep the adult social care service going. They are a national but neglected source of expertise, skills and knowledge.

Full report: Adult Social Care Committee challenges government to urgent reforms. Easy to read version is also available.

You could read also: